1] Introduction

Regionalization refers to the intensification of political and economic interdependence among states and other actors within a specific geographic region. This process involves the formation of regional institutions or agreements, that facilitates collective action on shared interests, such as trade or security. This trend – the regionalization of world politics – has led to influential organizations like the European Union, ASEAN, and others shaping international affairs alongside global institutions like UN.

In this topic, we’ll start with defining key terms and concepts, we then examine why states pursue regionalization, its advantages and drawbacks, and what scholars like Karl Deutsch and Ernst Haas have said about it. Then, the article will analyse major regional organizations – from the EU and USMCA to ASEAN, SAARC, BRICS+, BIMSTEC, SCO, APEC, IPEF, and more – covering their origins, structure, achievements, challenges etc., and India’s engagement with each. Finally, we compare the success of the EU and ASEAN versus SAARC’s limitations, and evaluate whether regionalization is complementing or replacing globalization.

2] Defining Key Terms

Region: In international relations, a region is a geographically bounded area comprising a group of countries that share certain commonalities. Joseph Nye defined an international region as “a limited number of states linked by a geographical relationship and by a degree of mutual interdependence”. For example, South Asia or Southeast Asia can be considered regions due to geographic proximity and shared historical or cultural ties.

Regionalism: Regionalism, in international context, refers to the political and ideological commitment to cooperate and integrate with countries in one’s region. It involves a “common sense of identity and purpose” among states in a geographic area, often manifested through the creation of institutions and policies for collective action.

Regionalization: Regionalization is the process by which regions emerge and strengthen, through increasing interactions. It can be seen as the organic, bottom-up growth of regional interdependence, often in areas of trade or investment. Or it can be deliberate, led by the politicians and dealing with issues like security.

Regional Integration: Regional integration is the deepening of cooperation between states in a region through formal agreements and institutions. It often involves stages like free trade areas, customs unions, common markets etc. In simple terms, regional integration means countries voluntarily pooling aspects of their sovereignty to gain collective benefits (e.g. the EU’s single market or common currency).

Globalization: Globalization is the widening and deepening of worldwide interconnectedness in all spheres – economic, social, technological, and political. It refers to the increasing interdependence of countries across the globe. For instance, the WHO defines globalization as “the increased interconnectedness and interdependence of peoples and countries”.

3] Understanding Regionalization

As explained in the beginning, regionalization refers countries organizing themselves into regional groups for mutual benefit. While the phenomenon of regionalization is as old as global politics, in modern context, regionalization gained momentum especially after the Cold War. This was marked by a proliferation of regional trade agreements and organizations worldwide. Today, virtually every part of the globe has some regional grouping, reflecting the importance of the regionalization.

A] Why do countries pursue regionalization?

1] Economic Gains

By integrating markets with neighbours, countries can increase trade and investment, achieve economies of scale, and boost growth. Reducing tariffs and harmonizing rules regionally opens larger markets for businesses. For example, under NAFTA (now USMCA), trade among the US, Canada, and Mexico more than tripled from 1994 (when NAFTA cam in effect) to 2011, crossing the $1 trillion mark.

Regional blocs also give members greater bargaining power in global trade negotiations. This aspect is evident in the success of ASEAN and EU while dealing with rest of the world in economic terms.

2] Peace and Security

Regional integration is also pursued to foster peace and stability. The European Union is the prime example – its foundational purpose was to bind historically rivals so closely that war between them would become unthinkable. The phenomenon is also defined as security community.

3] Connectivity and Infrastructure

Neighbours often collaborate to improve connectivity – building regional transport corridors, energy grids, and communication links. Such projects are more efficient when planned regionally. The South Asian and Southeast Asian countries, through initiatives in SAARC (e.g. the SAARC Highway) or BIMSTEC, seek integrated road and rail networks to boost trade and people-to-people contact. Enhanced connectivity is seen as both a cause and effect of regionalization.

4] Cultural and Political Solidarity

Regions can also be bound by cultural, linguistic, or historical ties. Regionalism may be pursued to affirm a shared identity (such as pan-Arabism behind the Arab League, or Islamic identity in OIC – Organization of Islamic Cooperation).

The BRICS coalition (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) was partially motivated by a shared interest of emerging powers to challenge Western dominance in global financial institutions and advocate a multipolar order.

5] Strategic and Geopolitical Reasons

Joining a regional bloc can enhance a country’s strategic security and leverage. Smaller states gain more influence and protection by aligning with larger neighbours. For big powers, leading a regional initiative can extend their influence.

Geopolitical competition can thus spur regional arrangements – e.g. the United States promoting an Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) in part to counterbalance China’s economic clout in Asia, or India pushing BIMSTEC cooperation as an alternative to a stalled SAARC.

Sometimes regionalism can also be pursued defensively, to avoid isolation in a globalizing world – nations fear being left out, so they join the bandwagon.

B] Benefits of Regional Integration

When successful, regionalization offers numerous benefits to member countries.

1] Economic Growth

Integrated regional markets enable higher trade volumes, attract investment, and generate jobs. For instance, the EU’s single market has made the EU the world’s largest trading bloc. Intra-regional trade as a share of total trade is a good indicator of integration – it stands around 60% in the EU and about 25% in ASEAN, but only ~5% in South Asia (projected to further reduce with recent Indo Pak tensions).

Regional cooperation can also help develop regional value chains (e.g. automobile manufacturing spread across North American countries).

2] Peace and Conflict Prevention

By creating interdependence, regional integration reduces the likelihood of conflict among members. The EU has kept lasting peace in Europe since WWII, earning it the Nobel Peace Prize in 2012. ASEAN is credited with helping maintain relative harmony in Southeast Asia – the “ASEAN Way” of dialogue and consensus has prevented open conflicts despite historical animosities. Karl Deutsch’s concept of a security community highlights that tightly integrated regions develop norms of peaceful conflict resolution.

3] Stronger Collective Voice

Acting as a bloc gives countries more weight in global affairs. The EU speaks with one voice in many trade negotiations and has significant clout in the WTO. Small states in CARICOM or the Pacific Islands Forum coordinate to influence global climate policy, which individually they could not. BRICS countries, by coordinating through annual summits, have advocated for reforms in institutions like the IMF and World Bank to reflect emerging economies’ interests.

4] Sharing of Resources and Knowledge

Regional cooperation enables pooling of resources to tackle common problems. Examples include regional development banks (the Asian Development Bank, etc.). Technical know-how, best practices, and innovations can spread more easily among neighbours facing similar development challenges. India led CDRI (Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure) can also be cited as an example of same.

5] Cultural Exchange and Mobility

Many regional arrangements facilitate easier movement of people. The EU’s Schengen Area allows passport-free travel across much of Europe, fostering tourism, student exchanges, and a sense of European identity. Within MERCOSUR, citizens of member states face simplified visa requirements. ASEAN has initiatives for cultural exchange and plans (albeit limited so far) for skilled labour mobility. Such interactions enhance mutual understanding and can create a regional identity alongside national identities.

C] Limitations and Challenges of Regionalization

Despite its achievements and promises, regional integration faces significant limitations:

1] Sovereignty Concerns

Countries often resist ceding too much sovereignty to regional institutions. Deep integration (as in the EU) requires nations to accept collective decisions. Not all regions are willing to create strong supranational bodies. For example, ASEAN’s integration remains shallow partly because members insist on national sovereignty and non-interference (the “ASEAN Way”).

2] Asymmetry and Hegemony Fears

Power imbalances within a region can breed mistrust. Smaller countries may fear domination by a regional heavyweight. In SAARC, many members worry about India’s dominance (India forms ~70% of SAARC’s area, population and GDP), which has sometimes led neighbours to hesitate on initiatives that might increase India’s influence. Similarly, in MERCOSUR, Brazil and Argentina account for over 90% of the bloc’s GDP, leading to perceptions of unequal benefits.

3] Internal Political Conflicts

Regional organizations can also be paralyzed by conflicts between their members. The clearest case is SAARC: the India-Pakistan rivalry has effectively stalled the grouping. SAARC summits have not been held since 2014 because of these tensions, and planned agreements (like a regional motor vehicles accord) were derailed by member disputes. Likewise, GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council) unity was weakened by the Qatar diplomatic crisis of 2017–2021. When bilateral issues dominate, regional cooperation suffers.

4] Differing Levels of Development

Further, a wide economic disparities among members can also complicate regional integration. Less developed countries fear being swamped by goods from developed neighbours if barriers drop. In ASEAN, the CLMV countries (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Vietnam) needed special timelines to implement free trade commitments compared to other members. Without mechanisms to address inequality (like the EU’s structural funds that aim to reduce regional disparities in income, wealth and opportunities in EU), integration can yield uneven gains and political backlash.

5] Compliance and Implementation Gaps

Signing treaties is one thing; implementing them is another. Many regional agreements face poor implementation due to lack of enforcement, e.g. ASEAN is known for its often-opted non-binding mechanisms. In such instances, progress relies on voluntary compliance. South Asian states signed SAFTA (South Asian Free Trade Area) in 2004, but numerous exemptions and slow implementation kept intra-SAARC trade minimal.

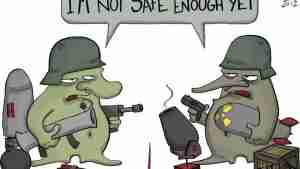

6] External Pressures and Global Trends

Regionalization doesn’t occur in a vacuum – global economic trends can also strain regional deals. Geopolitically, great-power rivalry can intrude: for instance, U.S.-China competition in Asia puts stress on ASEAN unity as states get pulled in different directions. Furthermore, if global trade rules are working well, the added value of a regional deal might be less; but if global talks stall (like the Doha Round’s failure), countries may over-rely on regional and bilateral deals, leading to a fragmented trading system. Thus, the success of regional initiatives can wax and wane with global conditions.

D] Theoretical Insights

Political scientists have long studied regional integration, yielding insights that illuminate these trends.

Early integration theorists like Karl Deutsch and Ernst B. Haas provide optimistic frameworks for regionalization.

Deutsch argued that increasing transactions and communication lead to a security community in which war becomes unlikely, highlighting the sociological aspect of integration (shared community values).

Ernst B. Haas, in his work The Uniting of Europe, explains regional integration through his theory of neofunctionalism. He argues that states integrate not just due to ideals or power politics, but because domestic actors find functional cooperation useful. When integration succeeds in one area, it creates pressure to integrate in others—called the “spill-over” effect.

Haas later links this process to constructivism, showing that interests and identities can change over time. He admits integration is not always smooth—there can be pauses or reversals. Still, he sees it as a peaceful way to reshape politics, where states willingly share sovereignty through trusted institutions.

E] Old vs. New Regionalism

The concepts of old and new regionalism represent two distinct phases in the study and practice of regional integration.

1] Old Regionalism

Old regionalism emerged in the aftermath of the Second World War and continued through the Cold War. It was largely driven by security concerns, geopolitical alignments, and state-centric interests. This form of regionalism was deeply embedded in the bipolar world order led by the United States and the Soviet Union. Regional organizations served as tools for consolidating ideological blocs (e.g. NATO in the West, Warsaw Pact in the East).

Economically, old regionalism was often protectionist, focusing on internal trade preferences and tariffs to create economic blocs. Integration was top-down, led by state elites and focused on achieving hard political or economic goals, such as tariff unions or defence pacts.

Key examples include the European Economic Community (EEC) in its initial phase and Latin American Free Trade Association (LAFTA), as well as Non-Alignment Movement (NAM) led by India. The European project, however, later evolved into a broader model that also served as a basis for new regionalism.

Prominent scholars associated with this phase include: Ernst B. Haas – Known for developing neofunctionalism, focusing on spill-over effects in regional integration. Karl Deutsch – Introduced the idea of security communities, where war becomes unlikely among integrated states. Joseph Nye – Analysed regional integration in terms of institutional arrangements and elite cooperation.

2] New Regionalism

New regionalism gained momentum after the end of the Cold War, rise of globalization, and the need for flexible, issue-based cooperation. Unlike old regionalism, this phase is more multi-dimensional, involving not just states but also non-state actors such as businesses, civil society, and regional institutions.

New regionalism is often open to the global economy. It is bottom-up to some extent, as integration often responds to social and economic demands from within the regions.

New regionalism also shows more overlapping memberships, and it also allows for variable geometry—members can integrate at different levels and speeds.

_________________________________________________________________________________

With this context, we now turn to specific regional organizations across the world, examining how each exemplifies regionalization – their history, structure, achievements, shortcomings, and India’s engagement with them.

4] European Union (EU)

A] Origin and Purpose

The European Union is often considered the gold standard of regional integration. The motivating vision was to bind European nations economically so as to secure lasting peace after the devastation of two world wars.

The Integration began in the coal and steel industries (European Coal and Steel Community, 1951) and gradually expanded. In 1957, the Treaty of Rome established the European Economic Community (EEC), laying the groundwork for a common market.

The Single European Act of 1987 set the objective of establishing a single market, emphasizing the “four freedoms”: movement of goods, services, capital, and people.

The Maastricht Treaty of 1992 formally established the European Union, adding political union elements (foreign policy cooperation, eventual common currency) to the economic community.

The Lisbon Treaty of 2007 reformed EU institutions. The Treaty first time clarifies the powers of the EU. It also gave EU a full legal personality, enabling it the ability to sign international treaties in the areas of its attributed powers or to join an international organisation.

In 2012, the EU was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for its role in promoting peace and democracy in Europe.

While EU still maintains its position, 2020 marked the first event when a country (UK) left the union.

B] Structure and Functions

The EU has a unique supranational governance structure. Key institutions include the European Commission (executive bureaucracy), the European Council (heads of government of member states), the Council of the EU (ministers of member states, legislating on behalf of national governments), the European Parliament (directly elected MEPs), and the European Court of Justice (ensuring EU law is uniformly interpreted and enforced).

Through these institutions, binding laws and regulations are adopted that supersede national laws in agreed domains. The EU functions as a single market – tariffs between members are zero, there is a common external tariff (customs union), and regulations are largely harmonized.

Twenty members form the Eurozone, sharing the euro currency and a common monetary policy run by the European Central Bank. Additionally, the Schengen Agreement allows passport-free travel across 26 European countries (most EU members plus a few others). The EU also has joint policies in agriculture (the Common Agricultural Policy), regional development, competition, environment, and more.

In foreign affairs and defence, integration is less unified but the EU does have a High Representative for foreign policy and conducts common foreign policy stances by consensus (for example, joint sanctions on Russia).

This pooling of sovereignty – often referred to as “supranational” integration – is what distinguishes the EU from other regional bodies that remain purely intergovernmental.

C] Achievements

The EU’s achievements are considerable, fundamentally transforming Europe:

1] Peace and Political Integration

The EU has fulfilled its original promise of maintaining peace among its members – Western Europe has seen no wars among EU members since integration began. Former rivals (France and Germany, etc.) became close partners. Further, the EU’s role in consolidating democracy is notable: it provided a framework for stable democratic transitions in Southern and Eastern Europe

2] Single Market and Economic Powerhouse

The creation of the single market (completed by 1992) eliminated internal trade barriers and standardized regulations, unleashing economic efficiencies. With a combined GDP of around $20 trillion (second only to the US) and 450 million people, the EU is an economic superpower. Intra-EU trade comprises about 61% of total trade, indicating a very high level of integration.

The free movement of labour has allowed workers to find jobs across the union and helped address skill gaps. Leveraging its market size, EU has also negotiated collectively many free trade agreements with partners like Japan, Korea, etc., with talks for India-EU FTA in process.

3] Euro Currency

The introduction of the euro is a landmark in monetary integration. 20 EU countries share the euro as official currency, making it one of the world’s major currencies. This removed exchange rate risks and transaction costs within the Eurozone, facilitating trade and investment.

4] Social and Regional Cohesion

The EU has robust mechanisms to reduce inequalities – through its budget, richer countries contribute funds that are invested in poorer regions (Structural and Investment Funds).

All EU citizens have the right to live, study, work or retire in any EU country. As an EU national, for employment, social security and tax purposes, every EU country is required to treat you exactly the same as its own citizens. This has fostered a sense of common European identity.

5] Political Influence

Owing to its economic might, EU wields significant influence in global diplomacy and economics. It speaks as one in the WTO and often in climate talks (the EU was instrumental in the Paris Agreement push). Additionally, the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy facilitates joint missions and peacekeeping efforts, enhancing its role as a global actor. The EU model has inspired or informed other regional projects, showing what deep integration can achieve.

D] Limitations and Recent Challenges

Despite its success, the EU faces internal strains and criticisms:

1] Brexit and Euroscepticism

In 2016, the United Kingdom – long one of the more Eurosceptic members – voted to leave the EU, and formally exited in 2020. Brexit was driven by complaints of lost sovereignty and freedom to control immigration. This was a major blow, marking the first time a country left the union.

It exposed growing Euroscepticism (Euroscepticism simply means doubt or opposition to the EU and its policies) in parts of Europe fuelled by concerns over democratic accountability, and national identity. While no other country has followed the UK, populist parties in several members (France’s National Rally, Italy’s League, etc.) have questioned aspects of EU integration like the euro or migration policies.

2] Economic Disparities and Eurozone Issues

The Eurozone Crisis began around 2009 when several EU countries using the euro, especially Greece, faced major debt problems. Triggered by high government deficits and weak economic growth, countries like Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain, and Italy struggled to repay loans. Investors lost confidence, leading to high borrowing costs. The crisis exposed flaws in the Eurozone’s structure—countries shared a currency but lacked unified fiscal policies.

The richer northern members were hesitant to bail out the heavily indebted south without strict austerity conditions, causing political rifts. While the crisis was managed, it showed the difficulty of having economic union without full fiscal/political union. Unemployment and economic stagnation in some areas have persisted, feeding discontent. Eastern European members also feel a development gap with the West, though cohesion funds try to address this.

3] Migration and Internal Solidarity

The EU faced a refugee and migration surge in 2015–16 that put the principle of free movement under stress. Frontline states like Greece and Italy felt overwhelmed, and some members (Hungary, Poland, etc.) refused migrant relocation quotas. This raised questions about solidarity and shared responsibility.

The Immigration issue once again came to fore after the onset of the war in Ukraine, when migration reached a historic high of around 6.5 million in 2022.

Reaching a common asylum and immigration policy has been challenging due to divergent views. And the issues has also fuelled nationalist politics in many countries, giving rise to right wing politics.

4] Decision-Making Challenges

The EU’s requirement for consensus or qualified majority in many areas can lead to slow or blocked decisions. Important policies like foreign policy still often require unanimity – e.g. a single country can veto an EU foreign policy statement. This has sometimes made the EU appear weak on the world stage.

5] External Geopolitical Pressures

The EU’s neighbourhood is volatile – Russia’s actions (the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the invasion of Ukraine in 2022) forced the EU to unite on sanctions and reduce energy dependence on Russia. While the EU did manage a unified tough response, it underscored the EU’s reliance on NATO security guarantees since the EU itself has limited military integration.

In the economic realm, U.S.-China trade wars and technology rivalry pose dilemmas for Europe’s open economy and regulatory power. The EU is trying to chart “strategic autonomy” – being able to make independent decisions – but finds itself caught at times between great powers on various issues.

F] The Uniting of Europe by Ernst Haas

Till date, Ernst Hass remains a major scholar for explaining the integration of Europe. The study, The Uniting of Europe (pub. 1958), though rooted in the 1950s, continues to matter because it laid the foundation for neofunctionalism (NF)—a major theory in the field of regional integration.

Haas argues that the ECSC (Coal and Stell Community) represented the first time sovereign states voluntarily pooled parts of their sovereignty without coercion. This process of integrating states defied both classical realism and idealism in International Relations (IR). Haas sought to show a third way—neither power politics (realism) nor utopian law-based peace (idealism), but pragmatic, interest-driven cooperation rooted in institutional dynamics.

1] Neofunctionalism (NF)

Haas developed neofunctionalism as a direct challenge to dominant IR theories:

Against Realism: NF rejected the belief that states act only to maximize power in an anarchic international system. Thinkers like Morgenthau and Spykman viewed power as the primary law of politics. Haas critiqued this as narrow and outdated.

Against Idealism: NF also rejected the Kantian hope that law and diplomacy alone could secure peace. Haas found this naive and out of touch with real-world complexities.

Instead, Haas proposed a theory in which state preferences are dynamic and shaped by domestic pluralist forces. Integration occurs when societal groups and interest-based actors perceive supranational institutions as better platforms for realizing their goals. As these institutions succeed, they gain legitimacy, which fuels further integration—what Haas termed as the “spill-over” effect.

Core Assumptions of NF

- Disaggregation of the State: States are not unitary actors. They are composed of competing interest groups, bureaucracies, and parties.

- Rational Calculations, Not Fixed Interests: Preferences emerge from domestic political competition and are shaped by evolving values.

- Spill-over Dynamics: Success in one functional area (e.g. coal and steel) creates pressure to integrate related areas (e.g. energy, transport).

- Supranationalism by Choice: States voluntarily transfer competencies to supranational bodies when it aligns with their interests.

- Peace through Institutionalization: NF suggested that regional cooperation can gradually lead to political community, fostering peace without war or revolution.

2] From Functionalism to Constructivism

In a later re-evaluation, Haas connects neofunctionalism to emerging strands of constructivism in IR. Constructivism, with its focus on the social construction of interests and identities, complements NF’s attention to evolving actor preferences.

Haas notes that both approaches move beyond deterministic models like structural realism or rational-choice institutionalism (idealism).

This “pragmatic constructivism” accepts that actors:

- Are shaped by institutions and habits;

- Can change their goals after new experiences or failures;

- Are guided not just by material utility but also by values and norms.

Thus, regional integration is neither automatic nor linear—it is dependent on dynamic and evolving factors.

3] Toward a Theory of Macro-Level Change

Finally, Haas repositions regional integration as a pathway to broader international change. The central question becomes: How do sovereign states choose to be less sovereign? NF provides one answer—by relying on institutions that gradually expand their legitimacy and functional effectiveness. This not only reshapes the political landscape of a region but also offers a peaceful template for political transformation at the global level.

5] United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA)

A] Origin and Purpose

The United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement, or USMCA, is North America’s regional trade pact, which entered into force on July 1, 2020. It replaced the earlier North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) that had been in effect since 1994.

NAFTA was one of the first major cross-continental free trade agreements, joining USA, Canada and Mexico. NAFTA succeeded in dramatically boosting regional trade – between 1994 and 2011, roughly from $300 billion to over $1 trillion. It integrated supply chains, especially in industries like automobiles, agriculture, and electronics, where components began to flow seamlessly across the Rio Grande and the 49th parallel.

The purpose of updating NAFTA to USMCA was to add provisions on digital trade, intellectual property, labour and environmental standards, and above all to satisfy the American interests, which holds disproportionate bargaining power in the agreement.

B] Structure and Provisions

USMCA, like NAFTA before it, is primarily a free trade agreement (FTA) rather than a comprehensive political union. It does not create supranational institution like EU. Key features of USMCA include:

1] Tariffs and Market Access

USMCA maintains NAFTA’s achievement of zero tariffs on the vast majority of goods traded among the US, Canada, and Mexico. This means products can cross borders without customs duties if they meet rules of origin. There are some specific quotas (for example, USMCA allows Canada to maintain limited protection for dairy but increases quota access for US dairy farmers).

2] Rules of Origin

These rules dictate how much of a product’s content must be made within North America to qualify for tariff-free status. USMCA tightened these rules for autos – requiring 75% North American content (up from 62.5% under NAFTA) and also introducing that a certain percentage of the vehicle must be made by workers earning certain minimum hourly rate. This was aimed at incentivizing production in the US/Canada (higher-wage).

3] Labor and Environment Standards

In addition to rules of origin, USMCA also incorporated stronger labour provisions (in part to address concerns that Mexico’s lower wages gave it an unfair advantage). Mexico agreed to labour reforms (e.g. easier unionization), and the pact has enforcement mechanisms for labour rights violations – a significant upgrade from NAFTA’s side agreements. Environmental commitments were also enhanced, bringing those side accords into the main text, with obligations on issues like air quality, marine pollution, wildlife trafficking, and forestry.

4] Digital Trade and Modern Topics

NAFTA was signed before the internet era took off, so USMCA adds chapters on digital trade (for example, prohibiting customs duties on electronic transmissions, ensuring free flow of data across borders, and protecting internet companies from certain liabilities). It also updates intellectual property rules (longer copyright terms, stronger patent protections in pharma, etc.), and addresses new sectors like e-commerce which were absent in 1994.

5] Dispute Settlement

The USMCA keeps a system where countries can settle disputes with each other. But the old system that allowed private investors to sue governments (investor-state dispute settlement) has been mostly removed.

6] Review Rule

A new review rule has been inserted in USMCA. It says the deal will be reviewed every 6 years and can last up to 16 years unless renewed.

C] Achievements

Given USMCA is very new (only a few years old), its specific impacts are still unfolding. However, one can consider the overall achievements of the North American regional arrangement (NAFTA/USMCA continuum):

North America is one of the largest trading regions globally. The arrangement locked in open trade that facilitated immense growth. By 2019, just before USMCA implementation, trilateral trade had reached about $1.2 trillion annually. This was given a further push by USMCA and the regional trades stands at massive $ 1.8 trillion as of 2023.

Further, the agreement has contributed to development of robust supply chains spread across geographies. NAFTA helped Mexico industrialize significantly, while giving US and Canadian companies access to competitive production chains.

With USMCA, now e-commerce firms can operate seamlessly across the three markets. The labour provisions aim to ensure Mexican workers’ wages rise, which could level the playing field over time and boost their purchasing power (indirectly benefiting US/Canada exports).

By preserving integrated markets, the USMCA region can better compete with other major regions (like the EU or East Asia). Each country benefits: the U.S. gains secure access to Canada and Mexico (which buy over a third of U.S. exports combined), Canada gets guaranteed access to its giant southern market, and Mexico locks in investment and export opportunities with its wealthy neighbours.

The arrangement has so far contributed to North America’s ability to weather supply chain shocks, and ensured its economic growth.

D] Limitations and Challenges

Despite being one of the most successful trade blocs, NAFTA/USMCA face with certain limitations.

A major criticism of NAFTA was that while it boosted overall GDP, the benefits were not evenly distributed. Many U.S. manufacturing jobs, for instance, were lost or relocated to Mexico where labour was cheaper. Mexico’s gains were also uneven – its northern regions attracted industry and grew, but the south of Mexico remained relatively untouched. USMCA’s new labour provisions attempt to address some of this by improving wages in Mexico and ensuring more manufacturing content is in high-wage zones.

Compared to the EU or even MERCOSUR’s aspirations, USMCA is narrow in scope – it is about trade, not a broader political union. It does not, for example, ensure free movement of people. Instead what we’ve seen is tightening of immigration laws by the US administration.

It means that North American integration is shallow beyond economics. When disputes emerge in areas outside the agreement, they can strain relations. The pact itself also does not directly tackle development gaps, aside from hoping that market forces will alleviate them. In fact, the fears came true when a change in U.S. leadership policy nearly unravelled NAFTA. The new “sunset” review clause means if relations sour or a protectionist turn occurs, the pact could lapse after 16 years.

Although NAFTA helped Mexico industrialize, NAFTA was not paired with a massive development fund as the EU. As a result, poverty and lack of jobs in parts of Mexico and further south continue, contributing to migration pressures. USMCA still doesn’t directly address these broader development concerns.

6] Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)

A] Origin and Purpose

ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) was founded in 1967 with five members – Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and the Philippines with signing of the Bangkok Declaration. The impetus was to promote regional stability and cooperation during a time of Cold War tensions and regional conflicts.

ASEAN’s initial purpose was political: to foster a peaceful environment in Southeast Asia where member countries could focus on nation-building, and functional: to collaborate in economic and social development. Unlike the EU’s very integrationist goal from the start, ASEAN was more about cooperation than integration, emphasizing state sovereignty and non-interference (the “ASEAN Way”).

Over time, ASEAN expanded, bringing membership to 10 countries covering all of Southeast Asia. The purpose also evolved to encompass creating a community of Southeast Asian nations – eventually articulated in three pillars: the ASEAN Political-Security Community, ASEAN Economic Community, and ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community.

Particularly, the economic purpose grew, resulting in ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) agreement in 1992. Today, ASEAN’s purpose is both to maintain regional stability (it has a central role in wider Asia-Pacific diplomacy) and to realize an integrated economic community of 10 diverse nations, while preserving the independence of each.

B] Structure and Principles

ASEAN’s structure is relatively simple and intergovernmental:

The ASEAN Summit of heads of state/government is the supreme decision-making body, meeting at least twice a year. There, leaders set broad directions and can sign agreements. The ASEAN Coordinating Council (comprising foreign ministers) meets more frequently to coordinate policy among the community pillars.

Key ministerial bodies include the ASEAN Economic Community Council, Political-Security Community Council, and Socio-Cultural Community Council, overseeing respective portfolios, and various specialized ministerial meetings (e.g., finance ministers, defence ministers, etc.).

ASEAN operates by consensus and consultation (the famous “ASEAN Way” which emphasizes informal dialogue, minimal legalistic enforcement, and respect for sovereignty). This means all members must agree for major decisions, and there’s a norm of not criticizing each other openly. This consensus approach has helped keep unity among very different regimes from communist Vietnam to monarchical Brunei to democratic Indonesia.

C] Key Agreements Shaping Integration

the ASEAN Charter (which came into force 2008) set out principles and organs formally. ASEAN sought to become ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) by 2015, a single market and production base (free flow of goods, services, investment, and skilled labour).

In practice AEC has achieved tariff elimination largely (intra-ASEAN trade now >98% tariff-free), but non-tariff barriers remain. There is no customs union or common external tariff; each state has its own trade policy outward.

In socio-cultural cooperation, ASEAN has numerous committees on health, education, environment, disaster management etc., promoting collaboration (like the ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance on disaster management).

D] Achievements of ASEAN

ASEAN is frequently cited as one of the more successful regional organizations, especially in managing regional relations:

1] Maintenance of Regional Peace

Since ASEAN’s founding, there have been no wars between member states – a significant achievement given some had territorial disputes or historical animosities. ASEAN’s role in developing the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation (TAC) in Southeast Asia in 1976 established principles of peaceful coexistence. Essentially, ASEAN transformed Southeast Asia from a region of proxy conflicts and bilateral skirmishes in the 1960s into a zone where differences are handled at the table.

2] Economic Integration and Growth

Economically, ASEAN has spurred trade and investment integration. Intra-ASEAN trade has grown to about 25%. AFTA has reduced the costs for regional businesses, and ASEAN as a bloc attracted increasing FDI – often from multinational companies setting up regional supply chains.

The ASEAN Economic Community, though not fully realized, has harmonized many product standards, eased travel for businesspeople, and opened up services sectors gradually. The combined GDP of ASEAN is over $4 trillion (IMF 2025 estimate), making it the 4th largest economy globally.

3] Regional Diplomacy and Centrality

ASEAN’s perhaps most notable achievement is becoming the fulcrum of broader regional diplomacy. Collectively, ASEAN manages to engage big powers on its terms. ASEAN has successfully negotiated as a bloc large freetrade agreements with external partners like China, Japan, India, and others, boosting market access for members.

More recently, ASEAN’s convening power led to the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in 2020, a mega-FTA including ASEAN and five Asia-Pacific partners, creating the world’s largest trading bloc. Interestingly, RCEP was conceived at 2011 ASEAN summit.

These achievements underscore “ASEAN centrality” – the group’s ability to be at the centre of regional economic and security architecture.

Overall, ASEAN transformed Southeast Asia from a theatre of conflict into an example of regional amity and gradually increasing integration.

E] Limitations and Challenges

ASEAN’s consensus-driven, sovereignty-respecting model, while keeping the group together, also poses limitations:

1] Shallow Political Integration

ASEAN is not a supranational union – it has no authority to enforce compliance or override national decisions. This means agreements are often “soft” and members implement them at their own pace. The “ASEAN Way” of non-interference has also meant ASEAN is slow or unable to address internal issues of members that have regional impact.

A current example is Myanmar’s crisis: after the 2021 military coup in Myanmar (an ASEAN member), ASEAN formulated a Five-Point Consensus calling for dialogue and an end to violence, but the junta has largely ignored it. This has led to criticism that ASEAN is ineffective on hard political or human rights issues.

2] Economic Disparities and Limited Market Integration

While tariffs are mostly eliminated, non-tariff barriers (NTBs) remain in ASEAN, including differing product standards, import licensing, and other regulations that impede seamless trade. The ASEAN Economic Community goal of a single market is far from fully realized – intra-ASEAN trade’s share of total trade hovers around 25%, much lower than the EU’s ~60%.

Free movement of skilled labour is also limited in practice – only a few professions are mutually recognized, and language/qualification differences hinder mobility. Thus, a “single market and production base” touted in 2015 remains aspirational; ASEAN’s integration is still a patchwork, relying heavily on each government’s political will.

3] External Pressures

ASEAN is navigating great-power rivalries in its region – particularly between the US and China. Different member states have different alignments (e.g., Singapore and Vietnam lean toward US and India, to balance China, while Cambodia and Laos are closer to China). This strains ASEAN unity in foreign policy.

Additionally, ASEAN economies are very linked with outside markets (China, US, EU, Japan).

Maintaining centrality is also a challenge as external powers form new fora like AUKUS or the Quad in the Indo-Pacific – ASEAN must adapt to remain relevant as the main platform for regional cooperation.

4] Democracy and Human Rights Issues

ASEAN’s diversity of political systems – from democracies like Indonesia to communist one-party Vietnam to absolute monarchy Brunei – means it avoids value judgments on governance. This has sometimes drawn criticism that ASEAN ignores human rights abuse. ASEAN did establish a human rights commission (AICHR), but it’s toothless, and civil society often finds ASEAN processes opaque or unaccountable.

Seen from other angle, this criticism reflects a Western-centric lens that ignores regional context. ASEAN’s cautious approach stems from its respect for sovereignty and diversity—rooted in its belief in “Asian values,” as articulated by Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew, which prioritize order, harmony, and community over adversarial politics. For many ASEAN states, stability and development take precedence over liberal norms. Rather than weakness, we can also say that this reflects a Third World assertion of alternative modernities. Thus, ASEAN’s model, while imperfect, challenges Western hegemony in norm-setting and asserts a localized, culturally grounded approach to regional cooperation and legitimacy.

F] Scholarly Perspective

1] Kishore Mahbubani

A prominent Singaporean diplomat and scholar, authored The ASEAN Miracle: A Catalyst for Peace with Jeffery Sng. In this work, Mahbubani emphasizes ASEAN’s role in maintaining regional peace and fostering economic growth among diverse nations. He argues that ASEAN’s principles of consultation, non-interference, and consensus have been instrumental in its success, contrasting it with the European Union’s supranational approach.

2] Amitav Acharya

A leading scholar in international relations, introduces the concepts of “norm localization” and “norm subsidiarity” to explain ASEAN’s approach to regionalism. s

Acharya highlights how Southeast Asian leaders did not just accept transnational norms as is. Rather, where such transnational norms were in line with prior local beliefs, or “cognitive priors”, they were successfully “localized”.

Norm subsidiarity, on the other hand is concerned with the creation of new norms by local actors. This helps protecting the norm’s autonomy from violation and abuse at the international level. In contrast to localization, which is inward-looking, subsidiarity is outward-looking. This phenomenon, Acharya suggest have also been instrumental in success of ASEAN.

7] MERCOSUR (Southern Common Market)

MERCOSUR is a regional bloc in South America. It was established by the Treaty of Asunción in 1991, originally signed by Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay. (Venezuela joined as a full member in 2012 but has been suspended since 2016 due to political issues.) Bolivia joined in 2024.

The core purpose of MERCOSUR is to promote free trade and the fluid movement of goods, people, and currency among member countries. Beyond economics, there is also a political intent: cementing friendly ties between former rivals (particularly Argentina and Brazil) and presenting a more unified bloc in international negotiations. The Asunción Treaty’s preamble speaks to the goal of “accelerating their economic development with social justice” and “improving the living conditions of their peoples” through integration.

A] Structure and Functions

MERCOSUR’s structure is intergovernmental and relatively light compared to the EU. The highest decision-making body – Common Market Council, is composed of foreign and economy ministers (and sometimes heads of state at summits). It sets major policy directions and can approve agreements.

The Common Market Group is the executive body, essentially coordinating implementation. It’s composed of representatives from each member state’s government (Foreign Ministry, Economy, Central Bank, etc.).

Apart from these, there are also various working subgroups on different sectors (industry, agriculture, customs procedures, technical standards, etc.) that harmonize regulations.

In terms of functions, MERCOSUR has implemented a customs union: it has a Common External Tariff (CET) on most imports from outside the bloc (with some exceptions and temporary flexibilities). Within MERCOSUR, roughly 90%+ of intra-trade is duty-free. The bloc aimed for a common market (free movement of goods, services, capital, and people). Goods and services move quite freely now, and there are residence agreements allowing citizens of one member to live and work in another with relative ease (though not as frictionless as the EU’s freedom of movement).

MERCOSUR also coordinates trade negotiations as a bloc – e.g., negotiating as one with other countries or groups. A notable example is the long-discussed MERCOSUR-EU trade agreement, which after two decades of talks was signed recently. The deal is the EU’s largest ever and Mercosur’s first with a major trading partner.

B] Achievements and Challenges Before MERCOSUR

Over the years, MERCOSUR has achieved notable successes, including a tenfold increase in intra-bloc trade during its first decade. The bloc has also played a role in promoting democratic governance and political stability in the region.

However, MERCOSUR faces several challenges. Although the intra-regional trade has increased, as of 2024, intra-MERCOSUR trade—accounts for just over 10% of the bloc’s total exports. This represents one of the lowest shares since MERCOSUR’s establishment, reflecting a long-term decline.

The decline in intra-regional trade is attributed to several factors, including increased focus on extra-regional markets, particularly China and the European Union. China is MERCOSUR’s largest trading partner, accounting for 27% of the bloc’s external trade, while the EU accounted for about 17%

Another significant issue is the disparity in economic development among member states, leading to asymmetrical benefits and tensions. Additionally, the bloc has struggled with internal disagreements, such as Uruguay’s pursuit of unilateral trade agreements, which conflict with MERCOSUR’s collective negotiation approach.

MERCOSUR represents an important piece in the puzzle of global regional blocs. While it has not achieved the cohesiveness of the EU or even ASEAN, it remains a significant regional market with future potential.

8] Caribbean Community (CARICOM)

The Caribbean Community (CARICOM), established in 1973, ensures cooperation among its 15 member states. Key achievements include the establishment of the CARICOM Single Market and Economy (CSME), which facilitates the free movement of goods, services, capital, and of skilled professionals across member states.

CARICOM has also been effective in coordinating foreign policy, allowing member states to present a unified stance in international forums. This collective diplomacy has amplified their voices on global issues such as climate change and nuclear proliferation.

Additionally, functional cooperation in areas like education, health, and disaster management has been bolstered through institutions like the University of the West Indies, the Caribbean Public Health Agency (CARPHA), and the Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency (CDEMA).

Despite these accomplishments, CARICOM is not free from challenges. Like other regional organizations, there is disparity in economic development among member states. At times, the Implementation of agreed-upon policies lag, hindering the full realization of the CSME. Also, due to small nature of these economies, resource constraints and reliance on external funding further impede the progress of regional initiatives.

Moreover, the diversity among member states—in terms of size, language, and economic structure—complicates consensus-building and policy harmonization. For instance, while some countries benefit from high external tariffs protecting local industries, others reliant on imports or tourism find such measures disadvantageous. Additionally, the phenomenon of brain drain, where skilled individuals emigrate for better opportunities, continues to challenge the region’s human resource capacity.

Overall, CARICOM has achieved notable progress in fostering regional integration, it must address internal disparities, enhance policy implementation, and strengthen institutional capacities to overcome existing challenges and realize its full potential.

9] Conclusion

In sum, the regionalization of world politics is a defining feature of the contemporary international system. Regions have emerged as significant theatres for cooperation, enabling countries to jointly tackle issues of development, security, and identity in ways that the global level sometimes cannot. Concepts like regional integration and regionalism help explain why nations cluster together – to gain strength in numbers, enhance peace with neighbours, and achieve collectively what they may struggle to individually. We examined how this plays out in major regional organizations across the globe:

- The European Union exemplifies deep integration, transforming a war-torn continent into a union with supranational governance – the most successful case of regionalism yielding peace and prosperity, albeit facing new tests like Brexit and internal divisions.

- In contrast, the South Asian SAARC shows how regionalism can falter due to political rivalries, as South Asia’s potential remains unrealized under SAARC’s banner, pushing members like India to seek alternative avenues.

- ASEAN demonstrates a middle path – a flexible model of cooperation respecting sovereignty but still delivering stability and incremental integration in Southeast Asia, now serving as a hub for broader Asia-Pacific frameworks.

- Mercosur and CARICOM highlight the efforts in Latin America and the Caribbean to unify markets and policies, finding mixed success – effective in fostering dialogue and some economic ties, but limited by asymmetries and external vulnerabilities.

- Cross-regional coalitions like BRICS show that regional proximity isn’t the only basis of grouping – common interests among emerging powers can create a platform to reshape global governance debates, a different facet of regionalization (“inter-regional” cooperation, so to speak).

- Meanwhile, initiatives like BIMSTEC illustrate the adaptive strategies of countries to form sub-regional cooperation when larger regional setups stall, as India and neighbours build connectivity linking South and Southeast Asia through the Bay of Bengal.

Throughout these cases, India’s role has been prominent. India’s engagements tell a story of a country leveraging regional platforms for both immediate neighbourhood goals and extended foreign policy interests. From championing SAARC’s vision but then turning to BIMSTEC when SAARC failed, to actively participating in ASEAN-led fora and BRICS, India balances multiple regional affiliations. For India, regionalism complements its global aspirations – a stronger neighbourhood and inter-regional network bolsters India’s case as a leading power on the world stage.

Finally, the relationship between regionalization and globalization appears to be largely symbiotic. Regional blocs often serve as “building blocks” of the global order – providing stability and cooperation in their regions which feed into a more orderly world. They also serve as “safety nets” or alternative forums when global consensus is elusive, thereby sustaining the momentum of international cooperation. While care must be taken to ensure regionalism remains open and inclusive, the evidence suggests that effective regional cooperation actually reinforces global integration rather than undermining it.

In an era of complex interdependence, the approach to governance has become multi-layered. Global problems (climate change, pandemics, financial crises) require global solutions, but regional collaboration can make those solutions more feasible and tailored. Instead of “regionalization versus globalization,” the paradigm is shifting to “regionalization as a pillar of globalization.” As the UPSC-related discourse emphasizes, a country like India benefits from both – a strong region around it and a well-functioning multilateral system beyond. Thus, pursuing regional initiatives (like the International Solar Alliance or BIMSTEC Grid or an African Union trade pact) and global initiatives (Paris Accord, SDGs, WTO reforms) are parallel, reinforcing tracks.

To conclude, the world is not replacing globalization with regionalization; rather, it is layering regional frameworks atop the global foundation, in a complementary fashion. Regional organizations provide the means for countries to pool sovereignty in manageable circles, build trust, and achieve collective gains, which in turn position them to contribute more confidently on the global stage. The success of regional bodies like the EU and ASEAN in fostering integration and stability showcases what regionalism can deliver, while the struggles of SAARC offer cautionary lessons on the impediments to avoid (chiefly, unresolved conflicts). For India and many nations, smart diplomacy involves strengthening regional cooperation (whether through economic integration, connectivity, or political dialogue) as an enabler – not an adversary – of a stable, prosperous, and cooperative global order.

hi,

did not find details of SAARC and BIMSTEC in this part.

are they discussed elsewhere ?

Oh yes.. we’ve discussed them under section 2B. This is the link : https://politicsforindia.com/3-1-saarc-and-bimstec-psir/