1] Historical Background of Arunachal Pradesh

A] Geography and Early History

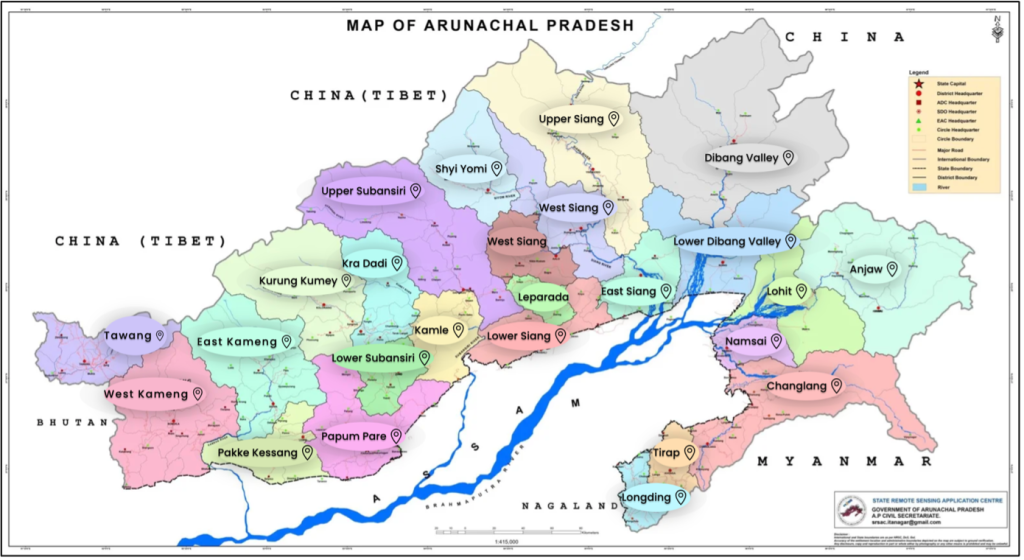

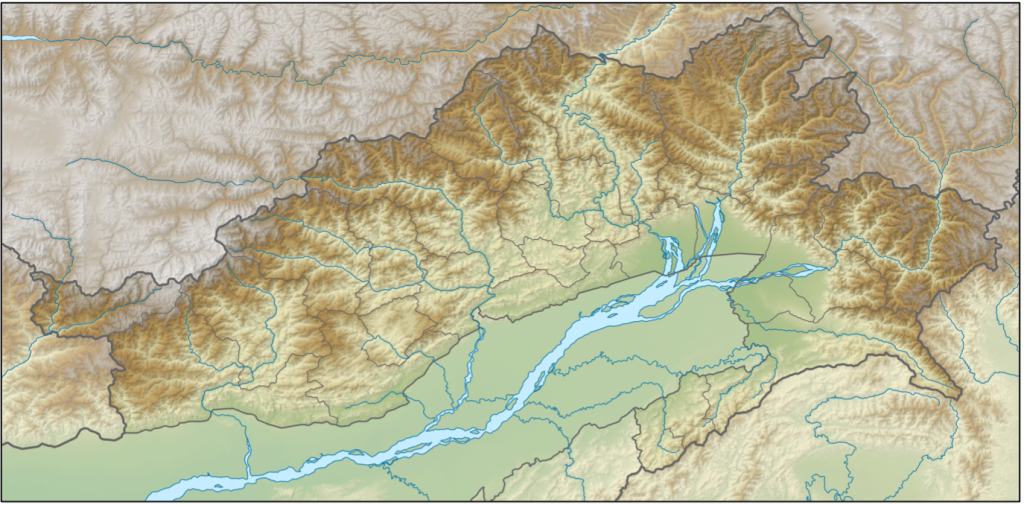

Arunachal Pradesh is a rugged Himalayan frontier in India’s northeast, long isolated by geography and home to numerous tribal communities. The region’s steep terrain and dense forests historically hindered large-scale governance, allowing tribes to maintain autonomous sociocultural systems.

In the northwest, especially Tawang and West Kameng, Tibetan influence was pronounced, with local communities acknowledging the Tibetan authority, exemplified by tax collection and administrative appointments. The Tawang Monastery, founded in 1681, symbolised these ties.

Conversely, the southern and eastern foothills intermittently came under the influence of Assamese like the Chutia kingdom. Throughout history, much of the highlands remained self-governed.

The pre-colonial region was thus a mosaic of independent tribal domains, Tibetan monastic control in the west, and Assamese interactions in the plains.

B] British Annexation and the McMahon Line

Following a treaty with Myanmar in 1826, British India annexed Assam but initially avoided the frontier hills (including now Arunachal Pradesh). The British were primarily concerned with protecting the fertile Brahmaputra valley (tea plantations and trade routes) from tribal raiders.

Later in 1873, British introduced the Inner Line Permit. It authorised the government to define a so-called “Inner Line” beyond which “British subjects” (i.e., the people of the British Indian provinces) could not travel without a pass. The initiative was ostensibly to protect tribal lifestyles but in reality to shield colonial economic interests from tribal incursions.

It was only by 1912–1914 that the British began demarcating and administering the area, creating the North-East Frontier Tracts.

At the 1914 Shimla Conference, British India and Tibet agreed to the McMahon Line, which demarcated the boundary along the crest of the Himalayas, placing present-day Arunachal within British India.

China rejected the Shimla Accord, claiming Tibet lacked treaty-making authority. Nonetheless, the British treated the McMahon Line as the frontier, although their governance remained indirect, relying on tribal leaders and punitive expeditions rather than consistent administration.

C] Post-Independence Integration

After 1947, India undertook efforts to integrate the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) into its administrative framework. India’s “forward policy” saw military and civil posts established up to the McMahon Line. India gradually consolidated control.

Arunachal Pradesh attained full statehood in 1987.

2] India–China Dispute Over Arunachal Pradesh

China disputes the McMahon Line, claiming it was imposed by colonial Britain in collusion with a non-sovereign Tibet. From 1950, China has published maps including Arunachal (termed “South Tibet”) as its territory. India, since Nehru, has maintained that the McMahon Line constituted the legitimate boundary, dismissing China’s ludicrous claims.

The border dispute escalated with Chinese incursions in the 1962 Sino-Indian War. China launched a major offensive, temporarily occupying parts of NEFA, including Tawang, before unilaterally withdrawing to the McMahon Line.

India subsequently reasserted control and fortified its presence. Although large-scale conflict has been absent since, minor incidents persist.

China continues to assert that Arunachal is part of Tibet—now part of China—and refers to it as “Zangnan” (South Tibet). Its rationale includes historical religious and trade linkages, such as Tawang’s subordination to Lhasa.

India counters with both legal and practical claims: the Shimla Accord, uninterrupted administration since 1947, and full integration into Indian democracy. Arunachal’s residents participate in elections and governance under Indian law. De facto and de jure, India asserts unambiguous sovereignty.

India controls the entirety of Arunachal Pradesh; China controls none of it but continues to claim it. The Line of Actual Control (LAC) broadly follows the McMahon Line in this sector, though undefined on the ground. China has invested heavily in border infrastructure north of the McMahon Line, matched by India’s military build-up and road networks.

The stalemate persists—India asserts its territorial integrity, while China refuses to acknowledge Arunachal’s statehood.

3] China’s Renaming of Places in May 2025

In May 2025, China’s Ministry of Civil Affairs released a list of “standardized” names for 27 locations in Arunachal Pradesh, which Beijing refers to as Zangnan (South Tibet). This marked the fifth batch of such renaming exercises since 2017.

The list included a mix of topographical features like mountains, villages, mountain passes, rivers, lakes etc. These were given Mandarin Chinese names.

India categorically rejected the move, calling it “vain” and “preposterous” and “meaningless propaganda exercise”.

Interestingly, each naming exercise has coincided with events that irked China: the Dalai Lama’s 2017 visit, Vice President Naidu’s 2021 visit etc. The 2025 timing—amidst India’s military tension with Pakistan—suggests deliberate strategic signalling, part of China’s broader toolkit of psychological and legal warfare.

Officially, China frames the renaming as an administrative measure: the Ministry of Civil Affairs is “standardising” place names for administrative clarity. However, this rationalisation belies deeper strategic motives—tied to narrative-building, legal positioning, and geopolitical pressure.

4] Strategic Analysis of the Renaming

A] Legal and Psychological Warfare

Renaming locations forms part of China’s “Three Warfares” strategy—legal, psychological, and media. By publishing Chinese names, Beijing creates a paper trail of administrative continuity. This may serve future diplomatic or legal arguments, even if control on the ground remains unchanged. A constructivist would note that repeated assertion can, over time, shape reality or at least public belief.

B] Domestic Nationalism and Symbolism

Renaming also serves to stoke nationalistic sentiment within China. It signals to Chinese citizens that the government is upholding territorial integrity, reinforcing the narrative of lost lands and colonial injustice. Further, this discourages any Chinese leader from appearing weak on territorial integrity, a core legitimacy issue for the CCP.

C] Pressure Tactics

From a Realist perspective, one could see these renaming episodes as part of applying pressure on India without resorting to force. A form of psychological warfare, aiming to unsettle India, to remind New Delhi that China has lingering leverage or claims, potentially to make Indian policymakers think twice about moves Beijing dislikes (e.g., high-profile visits to Arunachal, or strengthening ties with the U.S.).

D] Incremental Encroachment

Renaming can be a precursor in salami-slicing tactics—gradual steps to assert control without triggering war. China has a history of using incremental steps to solidify territorial assertions: in the South China Sea it started with maps, then names, then placed markers, then built reefs into islands, and finally militarized them – each step small enough to avoid war, but cumulatively altering the status quo.

India calls it “cartographic aggression” because it starts on maps and in nomenclature – a prelude to more tangible moves.

E] Retaliatory Signalling

Each renaming is often a reaction to Indian actions—Dalai Lama’s visit, strategic infrastructure, or diplomatic developments. In this lens, China’s deeper motive is to counter what it sees as India’s attempts to strengthen its hold on disputed land.

F] Strategic Messaging

Renaming counters any notion that the eastern sector is resolved. China might envision a future grand bargain where it could trade concessions – for instance, not pressing claims in Arunachal if India cedes claims in Aksai Chin. By inflating the importance of Arunachal through such naming and claims, China creates a card it could hypothetically relinquish for something else.

India, for its part, rejects this premise, since it claims both sectors and is not inclined to trade territory.

5] The U.S. Position on the Issue

The United States has unequivocally backed India’s stance on Arunachal Pradesh. Following China’s 2025 announcement, and indeed during previous episodes, Washington voiced strong opposition to China’s unilateral assertions.

A White House statement in April 2023 (after an earlier renaming of 11 places) exemplified this: “The United States recognizes Arunachal Pradesh as Indian territory and we strongly oppose any unilateral attempts to advance territorial claims by renaming localities.”

Additionally, in 2023, a bipartisan resolution was passed in the US Senate reaffirming that Arunachal Pradesh is an integral part of India.

From a Realist perspective, the US support for India here aligns with its grand strategy of balancing a rising China. The U.S. sees India as a crucial partner in the Indo-Pacific vis-à-vis China. By backing India’s territorial sovereignty, the US strengthens the broader coalition resisting China’s assertiveness.

States often ally against common threats; by visibly backing India, the US cements the perception of a de facto alignment with India against Chinese hegemony. This is part of a larger tapestry that includes the Quad, aimed at counterbalancing China in the Indo-Pacific.

The US might also see value in tying down China on multiple fronts. Encouraging India to be firm on the Himalayan frontier forces China to expend resources and attention there. A China that is heavily focused on its land border disputes might be less free to assert itself in, say, the South China Sea or against Taiwan, which are primary US concerns.

From an idealist or liberal perspective, the US backing can also be framed in terms of supporting democracy and international law, upholding sovereignty and rejecting unilateral changes to borders.

The US support can also be seen as an opportunity to cement ties with India.

6] India’s Strategic Response

India’s immediate response to China’s renaming gambit has been uncompromising rhetoric and diplomatic rebuttal. By calling China’s move “vain”, “preposterous”, and “cartographic aggression”, New Delhi signalled both to Beijing and the Indian public that it regards this as a propaganda stunt with zero validity.

In line with that, India did not alter any of its activities in Arunachal: infrastructure projects continued, political leaders plan visits as usual, and the state’s administration carried on calling places by their Indian names.

The elements of India’s grand strategy on the issue can be summed up as follows:

A] Strategic Autonomy but Closer Alignments

India doesn’t enter formal alliances, but it has moved closer than ever to the United States and other like-minded partners (Japan, Australia, France etc.) – something C. Raja Mohan describe as “aligning for own advantage while retaining independence.”

The effectiveness of this is evident: today, India has access to high-end military technology, intelligence sharing (e.g., under the BECA agreement, the US provides satellite imagery – useful in tracking Chinese moves), and diplomatic backing. This is arguably working as a force multiplier for India.

B] Deterrence by Denial

Militarily, India seems to pursue deterrence by denial – making it infeasible for China to achieve a quick victory or territorial grab. By fortifying the LAC, India wants to ensure any Chinese aggression would be costly and slow, allowing time for international pressure to kick in.

This is a rational strategy given India cannot match China troop-for, but can exploit difficult terrain and improving infrastructure on its side to deny easy gains.

C] Economic Resilience and Decoupling

India’s economic aspect of grand strategy is to become less dependent and more capable – essentially to boost comprehensive national power.

India also undertook a series of economic retaliations and decoupling moves aimed at China. While not directly about Arunachal, these form part of India’s broader strategy to reduce vulnerability to Chinese leverage.

For example, India banned over 200 Chinese mobile apps citing security concerns. It also tightened FDI rules to block Chinese investments in sensitive sectors. The idea is to limit China’s economic foothold which could translate into strategic dependency or influence.

Further, India’s relatively high economic growth is vital because to compete with China, India needs resources. Initiatives like Make in India, Digital India, etc., are geared toward this. India is indeed the world’s 4th largest economy now and has robust foreign exchange reserves, which provides stability.

However, its trade with China is still large and skewed. Reducing that dependence remains a work in progress.

D] Information Warfare and Tibet Card

India is increasingly active in countering Chinese narratives, using media, think tanks, and diaspora engagement.

The Indian government has also allowed more leeway for the Tibetan government-in-exile (based in Dharamshala, India) to be vocal, which irks Beijing. For instance, there was mention that the Tibetan exile administration might issue a map of Tibet that counteracts China’s version.

If India facilitates or even just tolerates such actions, it can be seen as a strategic use of the Tibet card. While India still officially recognizes Tibet as part of China, these subtle shifts – send signals to China that it does not hold all the cards.

7] Conclusion

The renaming of places in Arunachal Pradesh by China is emblematic of a broader contest: not just over territory, but over history, perception, and legitimacy. India’s response seeks to defend both its sovereignty and the principles of international order.

The dispute reflects a clash between post-colonial statecraft and revisionist ambition, where maps, names, and narratives become tools of strategic competition. Arunachal Pradesh remains firmly within India’s constitutional and administrative domain, and India’s strategy aims to ensure that no cartographic aggression can undermine this enduring reality.