1] Introduction

The 21st century has reshaped historically rooted India-Iran partnership. In the current context, India’s relationship with Iran holds immense strategic value, especially in areas such as connectivity, energy, and evolving geopolitics.

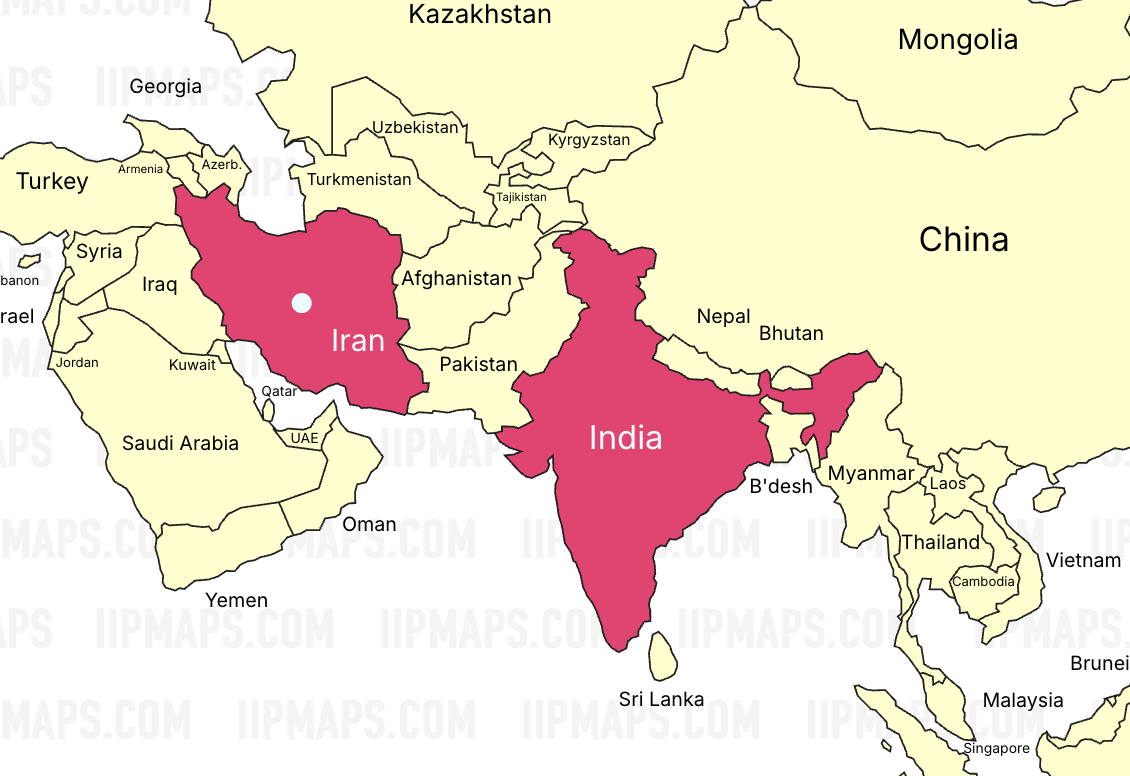

The location of Iran and India is pivotal in Asia. India is at the crossroads of the Indian Ocean and South Asia, and Iran bridges the Middle East, Central Asia, and the Caucasus. For India, this makes Iran crucial for regional connectivity and trade.

Consequently, the two infrastructure initiatives –Chabahar Port and the International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC) – have become linchpins of India-Iran Relations.

These projects also illustrate the converging interests of nations. Both countries strive to provide alternatives to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and want to reduce reliance on routes dominated by Western-aligned powers.

The Chabahar–INSTC nexus also serves as a geopolitical conduit. For India, it is a gateway to Afghanistan, Central Asia and Russia, in line with its “extended neighbourhood” outreach. For Iran, it is a means to counter sanctions, balance relations with multiple powers, and leverage its strategic location.

In 2024, both the countries signed the Chabahar Port Operational Agreement. This signals a renewed commitment to regional connectivity and economic integration amid intensifying great-power rivalry and regional instability.

2] Chabahar Port: Geopolitical Significance

Chabahar Port is a seaport situated in Iran on the Gulf of Oman. India has invested in the development and operation of the Shahid Beheshti terminal of the Chabahar port.

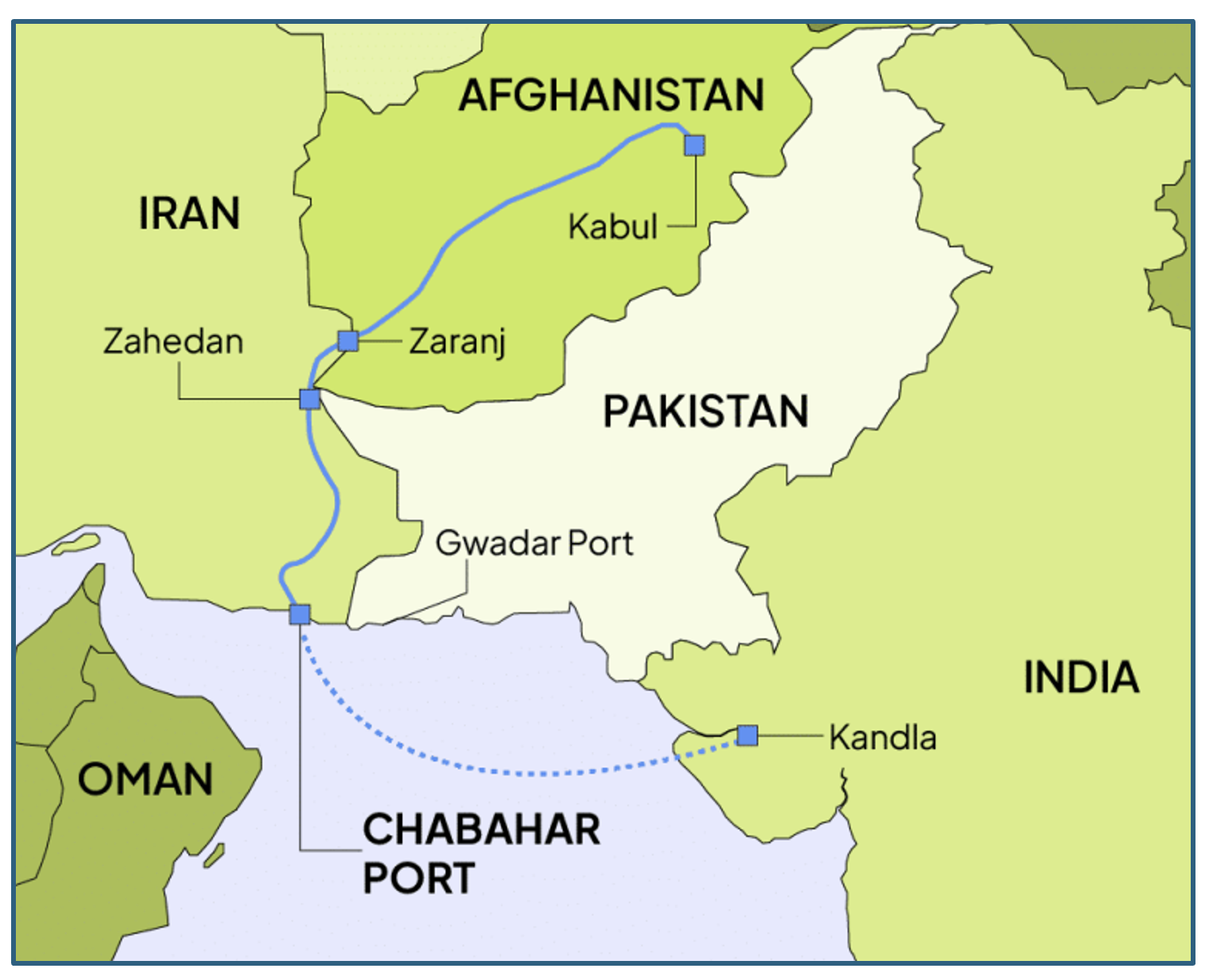

Chabahar’s geography is critical. It is Iran’s only oceanic port, and has direct access to the Indian Ocean. It lies merely about 170 kilometres west of Pakistan’s Gwadar Port and about 900 km from the Strait of Hormuz entrance. This positioning of Chabahar grants India direct access to Afghanistan and Central Asia, bypassing Pakistan.

Also, Chabahar is a port in friendly hands (Iran’s) where India is a welcomed partner. For decades, Pakistan has denied India overland transit to Afghanistan; Chabahar breaks this barrier.

India currently operates the port under a 10-year agreement. Indian officials describe this port as “a vital trade artery.”

3] Development and Comparison with Gwadar

Both Chabahar and Gwadar sit at the crossroads of the Middle East and South Asia often being called “sister ports.” Therefore, these ports are often objects of comparison in geopolitical discourse.

Gwadar Port, in Pakistan’s Balochistan province, is a flagship project of China’s BRI. China has invested heavily on it under the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

When compared to Chabahar, Gwadar’s planned capacity is enormous. Projections suggest that by 2030, it could handle 400 million tons of cargo annually, far eclipsing Chabahar’s planned capacity of 10–12 million tons.

There is even speculation about Chinese involvement in Chabahar. Iran has indicated that while India has exclusive rights to develop one of Chabahar’s terminals (Shahid Beheshti), other parts remain open for investment. As of 2024, however, China’s support to Chabahar has not materialized as speculated.

4] Recent Chabahar Operational Agreement

In May 2024, India signed a 10-year agreement with Iran to operate the Shahid Beheshti terminal of the Chabahar Port.

The agreement indicates India’s intent to “reposition itself in global trade networks.” With India’s economy growing and aiming for great-power status, having its own foreign port operations is a new dimension of power projection. It enhances India’s credibility as a connectivity provider in the region, offering alternatives to BRI.

For Tehran, the deal is both economically and diplomatically advantageous.

Economically, Iran gains a committed investor at a time when sanctions have scared off most foreign investors.

Diplomatically, partnering with India helps Iran balance its partnerships. Iran can now leverage ties with both India and China, rather than being overly dependent on Beijing. The Chabahar deal, coming alongside Iran’s existing ‘25-year comprehensive cooperation agreement’ with China, shows Tehran pursuing a multi-alignment strategy of its own.

Further, the diplomatic signalling of the May 2024 agreement extends beyond the bilateral realm. India effectively signalled that while it values U.S. partnership, it will not sacrifice vital regional interests at Washington’s behest. By formally anchoring itself in Chabahar, India challenges China’s monopolization of regional ports as well.

After the Taliban takeover of Kabul in 2021, India had lost its direct presence in Afghanistan. By developing Chabahar, India provides an outlet for Afghan goods and maintains a stake in Afghanistan’s economic future without physically being there. Central Asian republics, which have long sought diversified trade routes, have also welcomed progress at Chabahar.

5] The INSTC: Strategic Connectivity Redefined

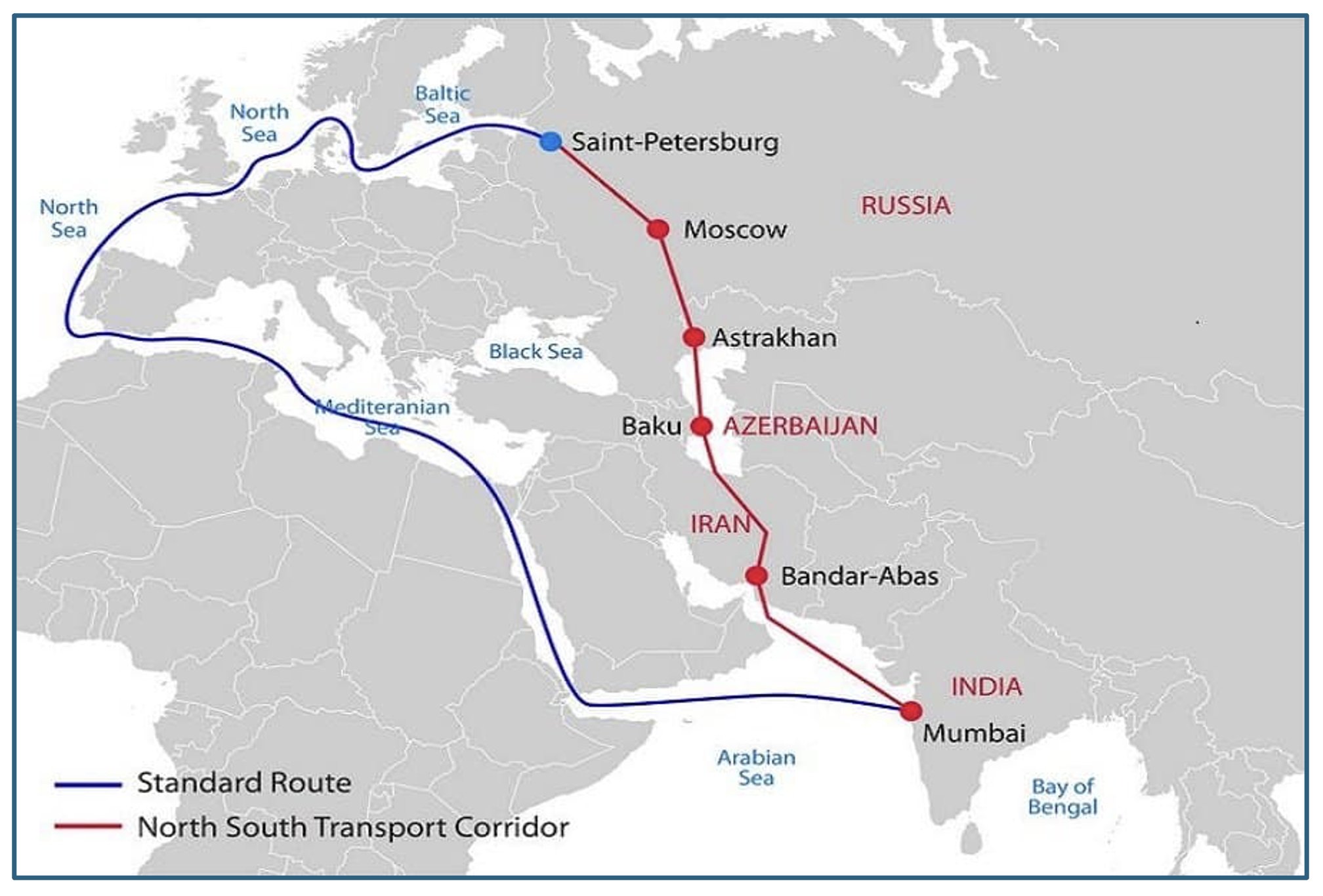

The International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) is a multi-modal transportation network that aims to connect South Asia with Central Asia, Russia, and Europe through the shortest possible overland route. Conceived in 2000 by India, Iran, and Russia, INSTC connects Mumbai to St. Petersburg via Chabahar, Bandar Abbas, and the Caspian Sea. It involves road, rail, and sea links.

While Chabahar was not part of the original INSTC blueprint but has been pragmatically integrated due to its direct sea connectivity to India and linkages to Iran’s road–rail network.

A] Strategic Advantages

The INSTC offers a cheaper and faster alternative to the Suez Canal route. It is also expected to significantly boost trade volumes among the involved countries.

By improving connectivity between India, Iran, Russia, and Central Asia, previously under-traded bilateral pairs could flourish. For example, India’s trade with Central Asia has been a fraction of potential due to lack of routes. INSTC opens these markets.

Another advantage is strategic flexibility: The corridor passes through countries that are friendly or neutral to each other, forming a contiguous chain outside Western control. This means the corridor’s use is less subject to geopolitical coercion by outside powers.

B] How INSTC Supports India’s Regional Leadership

While INSTC will boost connectivity, it is also a strategic instrument for India. It will help it to realize its ambition of being a continental as well as maritime power.

India has a stated “Connect Central Asia” policy (launched 2012) aimed at deepening ties with the five former Soviet republics. By moving goods through INSTC, India can substantially boost trade with Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, etc., which collectively have large energy reserves and markets for Indian pharmaceuticals, tea, textiles, etc.

As emphasized earlier, INSTC (especially via Chabahar) enables India to circumvent Pakistan for trade with Afghanistan, Iran, and Central Asia.

India also sees INSTC as one part of a larger network of connectivity that includes eastward routes. For instance, India is leading the Bay of Bengal Initiative (BIMSTEC) and the India-Myanmar-Thailand trilateral highway project. In this sense, India could become a transport linchpin linking Southeast Asia to Europe.

By championing INSTC, India strengthens its claim of being a leader of the “Global South” and a proponent of a multipolar order. It works with non-Western partners on an initiative that bypasses Western-controlled chokepoints. This resonates with many developing countries’ desire for more options. India’s External Affairs Minister Jaishankar often speaks of “post-NAM issue-based alignment”, where India aligns with various countries depending on the issue, rather than a rigid bloc.

6] West and Central Asia: India’s Balancing Act

India’s foreign policy in West Asia and Central Asia is often described as a tightrope walk – seeking positive relations with mutually antagonistic players. New Delhi has pursued a delicate balancing act involving Iran on one side, and the Arab Gulf states, Israel, and the U.S. on the other, all while extending its reach into Central Asia.

The principle guiding this is India’s doctrine of strategic autonomy and “multi–alignment” or “issue-based alignment”. As stated earlier, India engages with each country based on specific issues without entering exclusive alliances.

For example, India has consistently walked a tightrope between its relations with Iran and its strategic partnership with the United States. The reimposition of US sanctions after the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the JCPOA in 2018 severely curtailed India’s oil imports from Iran, which once stood at nearly 11% of its crude basket.

India, however, secured limited waivers in 2018–19 for Chabahar-related activities, recognising the port’s role in Afghanistan’s stabilisation. However, energy ties remain severely constrained.

This demonstrates neoclassical realism or pragmatism in Indian foreign policy – ideology is secondary to interest. India’s civilizational identity as a pluralistic nation also helps – it can genuinely claim cultural links with Iran (Persian influence), with the Arab world (Indian Ocean trade, Muslim population connections), and with Israel (historically no direct conflict and now tech synergy). This multi-civilizational connect gives India a certain acceptance in all camps.

7] Challenges and Missed Opportunities

Despite its promise, Chabahar’s full operational potential remains unrealised.

One of the most oft-cited problems is the glacial pace at which some India–Iran projects have moved, largely due to bureaucratic red tape and shifting priorities in New Delhi.

First agreed in 2003, the Chahbahar project made little headway for over a decade. Even after 2016’s impetus, Indian bureaucracy moved slowly in disbursing funds and delivering equipment. Iran, frustrated by the lack of execution, has occasionally considered alternative partnerships.

Iran’s domestic protests, economic crisis, regional conflicts and susceptibility to sabotage (e.g., targeted assassinations and cyberattacks) have created an uncertain investment environment. Continued U.S. financial sanctions on Iran adds to the uncertainty.

Chabahar Port is also facing external competitions. For example, China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Gwadar’s fast-paced development present a direct challenge to Chabahar.

Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Central Asia with Chinese backing have promoted an “Middle Corridor” that goes from China to Kazakhstan, bypassing both Russia and Iran. If it develops, some of the cargo that might go via INSTC could instead go that way.

Iran’s 25-year strategic deal with China (2021) and increasing energy cooperation with Russia have complicated India’s space in Iran’s foreign policy matrix. China is looking forward to invest in Iran. Compared to China, India’s logistics has some weaknesses. Chinese companies are world leaders in port management and shipping, whereas India is new to it. India will need to up its game to ensure INSTC routes are reliably faster & cheaper as promised.

Nevertheless, Iran has welcomed India’s investments as a counterbalance to overdependence on any single power.

8] Prospects and Future Roadmap

The May 2024 agreement marks a significant turning point, institutionalising India’s role in Chabahar for at least a decade. This gives investors and policymakers time and incentive to develop long-term trade and transit plans.

Additionally, India can take other measures as well.

India could integrate INSTC with other regional initiatives such as the EAEU, BIMSTEC, and even the India–Middle East–Europe Corridor (IMEC) proposed at G20 2023. Chabahar could be a maritime node linking IMEC to INSTC, enhancing India’s transcontinental logistics appeal.

To insulate Chabahar investments from bureaucratic delays, India could create a dedicated task force. India should also increase engagement with INSTC countries to ensure logistical synchronisation. Apart from that, strategic communications could be used to explain Chabahar’s stabilising role to the West. And at the end, India should Expand soft diplomacy (scholarships, training, cultural exchanges) with Iran to deepen people-to-people ties.

10] Conclusion

Chabahar Port and the INSTC stand as practical illustrations of India’s evolving foreign policy doctrine: one that blends strategic autonomy, regional connectivity, and long-term economic statecraft. While geopolitical uncertainties persist, especially regarding US–Iran tensions, ongoing conflicts in West-Asia and China’s growing influence, India’s investment in Chabahar reflects its resolve to shape Eurasian geopolitics on its own terms. If supported by consistent policy implementation and multilateral engagement, Chabahar and INSTC could become enduring pillars of India’s continental outreach and strategic diversification in the emerging multipolar world.