1] Introduction

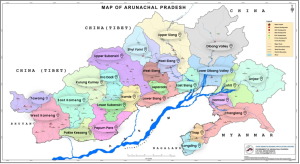

Operation Sindoor was a brief but intense military campaign launched by India on May 7, 2025, in retaliation for a major terrorist attack at Pahalgam in April 2025. Over four days of hostilities (May 7–10), India carried out precision missile and air strikes against militant targets deep inside Pakistan and Pakistan-occupied Kashmir.

The campaign was followed by fierce exchanges of fire, drone incursions, and missile attacks between India and Pakistan before a ceasefire was brokered on May 10.

Operation Sindoor is widely seen as a strategic inflection point in South Asia. It marks India’s clear departure from its traditional posture of reactive restraint vis-à-vis Pakistan toward a new doctrine of proactive deterrence. In contrast to previous episodes where India absorbed terror attacks or responded covertly, Sindoor involved overt, cross-border use of force at a scale not seen since the 1971 war.

The Indian leadership framed the operation as a justified act of self-defense and signaled that such military responses to terrorism would henceforth be the “new normal”.

Such rhetoric and action represent a stark departure from India’s past policy a decade ago, when strategic restraint was the norm and fears of escalation often limited military options.

2] Historical Context of India–Pakistan Relations

India and Pakistan’s relationship since 1947 has been marked by periodic wars, military standoffs, and an enduring rivalry centered on the disputed region of Kashmir. For much of this history, India’s approach could be characterized as one of strategic restraint, especially in the face of provocations by Pakistan or its proxies.

Despite fighting full-scale wars in 1947–48, 1965, and 1971, and a localized high-altitude conflict in Kargil in 1999, Indian leaders often chose to limit the scope or intensity of conflicts, mindful of international pressure and the risks of escalation (which, after 1998, included the spectre of nuclear war).

Similarly, following the brazen 2001 Parliament attack, India mobilized its army but ultimately pulled back from crossing the international border. And in the wake of the Mumbai 26/11 attacks in 2008, which killed over 170 people, India again exercised restraint by not launching military reprisals, focusing on building international pressure on Pakistan to crack down on terrorist groups.

These episodes reinforced an international perception of India as a country that generally avoided knee-jerk military responses, even under grave provocation.

However, this paradigm of near-automatic restraint began to shift in the 2010s as India grew in economic and military strength and as domestic public opinion became less tolerant of perceived impunity for cross-border terrorism.

A turning point came after the 2016 Uri attack in Jammu and Kashmir, where militants killed 19 Indian soldiers. Breaking with past pattern, the Indian government authorized “surgical strikes” by special forces against terrorist launch pads just across the LoC in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir.

The next crisis, in February 2019, saw India push the envelope further. A suicide bombing in Pulwama (Kashmir) killed 40 Indian paramilitary police, and the Pakistan-based Jaish-e-Mohammed claimed responsibility. In retaliation, India carried out an airstrike on a JeM training camp at Balakot – deep inside Pakistani territory (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province), beyond the disputed Kashmir region. This was a dramatic escalation: it marked the first use of Indian airpower against Pakistan since the 1971 war, and notably the target (Balakot) lay in mainland Pakistan, not in Pakistan-administered Kashmir.

Against this backdrop, Operation Sindoor in 2025 did not emerge from a vacuum – it was the culmination of a steady evolution in India’s retaliatory doctrine. When a new major terrorist attack occurred – the Pahalgam massacre on April 22, 2025, in which 26 Indian civilians (mostly tourists) were killed – the stage was set for India’s most ambitious response yet.

After initial diplomatic steps (India blamed Pakistan-based militants of the LeT for the Pahalgam attack, suspended the bilateral Indus Waters Treaty, and warned of action), India’s military struck on May 7, hitting multiple targets across a broad geography: from Pakistan-occupied Kashmir to cities deep in Punjab province. It was, as analysts note, the deepest India has struck Pakistan since 1971, and the first time cruise missiles and armed drones were used by India in a fight against Pakistan.

3] From Restraint to Deterrence

For the first few decades after independence, India’s foreign policy and strategic culture were heavily informed by the ideals of its first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. Nehru championed non-alignment, Panchsheel (five principles of peaceful coexistence), and a general aversion to military adventurism, projecting India as a peace-seeking civilizational power. This Nehruvian idealism placed faith in diplomacy, international law, and moral leadership.

However, as India’s power grew and its security challenges mounted, a pragmatic reorientation became visible.

One reflection of this is how India defines “strategic autonomy” today. No longer couched as equidistance in a bipolar Cold War, strategic autonomy now means multi-alignment – engaging all major powers but aligning with none exclusively – and asserting India’s right to make independent decisions.

In the realm of security and military doctrine, this shift has manifested as a move from passive deterrence (or deterrence by denial, hoping to dissuade aggression by defense and diplomatic isolation) to active deterrence or deterrence by punishment.

Another aspect of India’s strategic culture evolution is the willingness to endure risk and accept losses if necessary. The Indian Air Force, true to the new ethos, neither confirmed nor denied specifics during the conflict, simply stating that “losses are a part of combat”. This stoic acceptance, show a break from the past, where fear of losses often paralyzed action.

4] Pakistan’s Response and the Shift in Bilateral Dynamics

Pakistan was caught in a difficult position by Operation Sindoor. India’s sudden, coordinated strikes on May 7, 2025 placed Islamabad under tremendous pressure to respond, both to safeguard its deterrence credibility and to assuage domestic outrage at the breach of sovereignty.

While Pakistan did retaliate robustly in the military domain, it also found itself largely on the defensive diplomatically. The crisis underscored an erosion of Pakistan’s credibility in international forums on the issue of terrorism and cast India as increasingly the agenda-setter in the rivalry.

Militarily, Pakistan’s narrative was that its riposte caused “major damage” to Indian installations. However, ground reality and later independent assessments paint a more modest picture of Pakistan’s military gains.

The fact that Pakistan did not immediately invoke its nuclear red lines (as it often had in the 2000s) may indicate it recognized India’s strikes were limited and precisely not targeting the Pakistani state directly.

In other words, India’s strategy somewhat constrained Pakistan’s legitimacy in escalating to the nuclear level, since India could credibly say it was hitting terrorists, not Pakistan’s military – thus, a nuclear threat would appear disproportionate and tacitly admitting linkage with the terrorists.

Finding itself in a position where overt nuclear posturing was off the table, Pakistan focused on conventional and informational retaliation. Its media and officials heavily pushed claims of tactical victories, like the shooting down of Indian jets. While some of these claims found traction in the moment – many were later disputed or unverified.

The credibility gap for Pakistan was most evident in the international diplomatic theatre. With countries like France explicitly acknowledging India’s legitimate concerns about terrorism. UNSC statements ended up being bland calls for restraint on both sides, which, as former UN diplomat Shashi Tharoor noted, “were effectively addressed mainly to Pakistan.”

On the other hand, India’s ability to set the agenda in the bilateral dynamic was evident in multiple ways.

First, India seized the initiative with the first strike. By doing so, it compelled Pakistan to respond to India’s action, rather than the historical pattern of India responding to Pakistan’s provocation. This flipped who was in control of escalation. This put Pakistan in a bind. If it did nothing, it would seem weak; if it retaliated too strongly, it risked blame for sparking a wider war.

Another manifestation of India setting the agenda was the range of non-kinetic punitive measures it unveiled. For example, after the Pahalgam attack and before Sindoor, India announced the suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty – a drastic diplomatic step never before taken. India also promptly closed its airspace to Pakistani aircrafts. During the crisis, India even shut down the Kartarpur Corridor. All this conveyed that India would not compartmentalize counter-terrorism and normal ties.

Crucially, India also won the battle of legitimacy to a great extent. By providing evidence of the strikes’ effectiveness (satellite images of destroyed camps) and consistently framing them as counter-terror ops, India made it hard for Pakistan to gain sympathy.

5] India’s Strategic Autonomy and the Decline of Swing-State Politics

For much of the post-Cold War era, analysts characterized India as a classic “swing state” in international politics. A country that could swing between alignment with the West and partnership with non-Western powers (like Russia or China) depending on the issue, thereby significantly impacting the global balance. India was courted by all sides but committed to none, maintaining a policy of strategic autonomy rooted in its non-aligned legacy.

However, recent years – and the episode of Operation Sindoor in particular – illustrate that India’s strategic autonomy has taken on a new form. Rather than “swinging” passively between poles, India is increasingly multi-aligning on its own terms.

Notably, India undertook the operation unilaterally, without seeking permission or support from any great power. In fact, there were reports that some Western diplomats quietly urged India to show restraint after Pahalgam, warning of nuclear risks. This willingness to “defy Western pressure” is a defining feature of the new Indian approach.

The trend can also be seen in India’s purchase of S-400 air defense or the ongoing imports of discounted Russian oil.

The concept of decline of swing-state politics implies that India is no longer content to be seen as a “prize” that either the Western camp or the China/Russia camp can swing to their side. Instead, India is positioning itself as a pole in its own right, with issue-based alignments. Jaishankar articulates this as “India will not be a pawn in anyone’s game; it will do what it takes to be a power on its own”.

India’s participation in groupings illustrates this multi-alignment: India is in the Quad with the US, Japan, Australia – a grouping implicitly balancing China – while simultaneously India is in BRICS with China and Russia pushing for multipolar financial structures.

During Operation Sindoor, India leveraged these multiple channels: it was able to count on the US and allies (Quad partners) to intervene diplomatically to stop Pakistan from escalating (the US making those calls), but it also leaned on Russia to not create any fuss and quietly support the anti-terror line, and used Middle Eastern ties to further corner Pakistan.

In fact, Indian officials have explicitly critiqued the “Global Swing State” label. They argue India is not swinging but rather shaping. A Carnegie Endowment piece titled “Non-Allied Forever: India’s Grand Strategy” notes India pursues multi-alignment to maximize options. What Jaishankar calls “multi-engagement.” One could say India has moved from “Non-Alignment 1.0” (Nehruvian, idealistic) to “Non-Alignment 2.0” or “Multi-Alignment” (pragmatic and interest-based).

Operation Sindoor underlined this because India simultaneously kept various partners in the loop without asking any one of them for material help. But it deftly used diplomatic support from all sides post-facto.

6] Theoretical Reflections

The evolution of India’s behavior as exemplified by Operation Sindoor invites reflection through various international relations (IR) theoretical lenses.

A] Realism vs. Nehruvian Idealism

For the first few decades after independence, India’s foreign and security policy was underpinned by what one could call Nehruvian idealism. Nehru and his intellectual peers believed in moral principles in international conduct – peaceful coexistence (Panchsheel), non-aggression, disarmament, Afro-Asian solidarity, and the elevation of international law and institutions (like the UN) over brute power politics.

However, as classical Realists would predict, when faced with persistent security threats and an anarchic international system, states eventually revert to power-maximizing behavior.

Operation Sindoor is a culmination of India “choosing realism” decisively over Nehruvian idealism. In stark contrast to Nehru’s reluctance even to retaliate when Portugal held onto Goa (India waited 14 years to liberate Goa in 1961, after exhausting diplomatic means), Modi’s India retaliated within 14 days of the Pahalgam attack.

The operation reflected core realist tenets of Statism, Self-help and Use of force as an instrument. India asserted its state interest (protecting its citizens and territory) as paramount. It did not rely on international community or UN to punish the perpetrators; it took action itself, epitomizing the realist idea that in an anarchic world, each state must ensure its own security. And at last, India employed force rationally to achieve a political goal – a very realist notion as opposed to idealists who treat war as aberration.

One might note that India’s realism is tempered by some idealist vestiges. India still professes commitment to international law (it carefully framed Sindoor as self-defense, not aggression), and it invests in soft power (yoga diplomacy, “Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam” – world is one family – as G20 motto).

But these idealistic flourishes seem more in service of pragmatic ends now, rather than ends in themselves.

B] From Non-Alignment to Multi-Alignment

While India has retained the doctrine of “strategic autonomy”, its meaning has evolved. Originally, strategic autonomy was essentially non-alignment – staying out of superpower blocs, to preserve independence in decision-making and uphold principles.

In the post-Cold War, as the world became unipolar and then multipolar, India has reformulated strategic autonomy as multi-alignment. This means actively engaging all major power centers to derive maximum benefit, while not being bound by any single one’s diktats.

Some observers say India’s approach now is “issue-based alignment”: partner with US on Indo-Pacific, with Russia on continental security, with EU on climate, with China on BRICS reforms, etc. This pragmatic flexibility is essentially “strategic autonomy 2.0”.

One theoretical concept that fits is Omni-balancing – leaders balance both external and internal threats via alignments. India multi-aligns externally (US/Russia/China) while also balancing internal needs (development, public opinion). Another concept is hedging: India hedges against uncertainty by not putting all eggs in one alliance basket, instead keeping options open.

C] Post-Colonial Theory and Politics of Recognition

Post-colonial perspectives emphasize how formerly colonized states seek to assert their identity and demand equal respect in a world historically ordered by colonial powers. India’s behavior can be partially seen through this lens.

During colonial rule and early independence, India’s voice was often marginalized by Western great powers. One can interpret Operation Sindoor as India asserting that it will not be restrained by Western opinion if its core security is involved – a stance many Western colonial powers themselves took in their interest.

This could be seen as India earning the “recognition” post-colonial states crave: being treated not as a subject of lectures on restraint, but as an equal power whose concerns (terrorism) are given weight.

Furthermore, post-colonial lens might interpret India’s multi-alignment as a refusal to accept the Western-defined binary of good vs bad states. India trading with Russia or Iran is a form of resisting Western dominance in norm-setting. It’s a pursuit of sovereign equality: India will decide its friends and foes, not follow what a Western-led order dictates.

7] Conclusion

Operation Sindoor is a watershed moment in India’s strategic trajectory – redefining the country’s approach to Pakistan and altering how the world perceives India as a power.

Operation Sindoor will be remembered as a defining milestone in India’s post-Cold War history – much as the 1971 war established India as the preeminent power in South Asia, the 2025 operation signaled India’s graduation into a power that doesn’t just react to the global order but actively shapes it. India has emphatically announced that it will set its own red lines and enforce them, global opinion notwithstanding.

To conclude, India has truly “arrived” – not only as the inheritor of a rich civilization and a champion of developing world voices, but as a hard power capable of and willing to act in defense of its interests. Operation Sindoor encapsulated this transformation.